A Scythe Across the Night Sky

This body of work is intended to evaluate, interpret and visually connote the ongoing destruction of antiquities and territorial conquest by the group calling itself Dawla Islamiya, or The Islamic State (ISIS, ISIL, DAESH, etc.). ISIS has captured large swaths of territory in Iraq and Syria. While the primary stated goals of ISIS is to erase the European Sykes-Picot borders established in the aftermath of World War I, and to re-establish an Islamic Caliphate meant to unite the Muslim world, they have also employed varying strategies of cultural and religious erasure, drawing attention to their status as jahaliiya, or a “state of ignorance” (of Islam). Their methods of addressing these artifacts have been two-fold. One is their most useful in terms of propaganda and antagonism, which is total destruction of these buildings and statues. The other has become one of the group’s most lucrative forms of income, which is their sale on the black market. There are many dynamics I am particularly drawn to examining here. But I will focus on two of the most intriguing. First, I am interested in ISIS’s apparent adherence to Sunni Islam’s traditional prohibition against images. The group destroys statues, such as Mesopotamian Lamasu, blows up temples such as the temple of Ba’al Shamin in Palmyra, Syria and publically displays the decapitated body of Khaled Al-Assad, the antiquities director of Palmyra who refused to tell the group where he hid hundreds of artifacts.

While ISIS proclaims the danger of craven images, they simultaneously film themselves “heroically” destroying these images, producing their own images. In fact, the media and propaganda element of ISIS is wholly dependent on the production and distribution of images. This contradiction produces an extraordinary tension regarding questions of representation and the meaning of a “dangerous image.” The second source of inquiry lies in the reemergence of Mesopotamian and pre-Islamic Gods and Goddesses as players within a military, cultural and political arena.

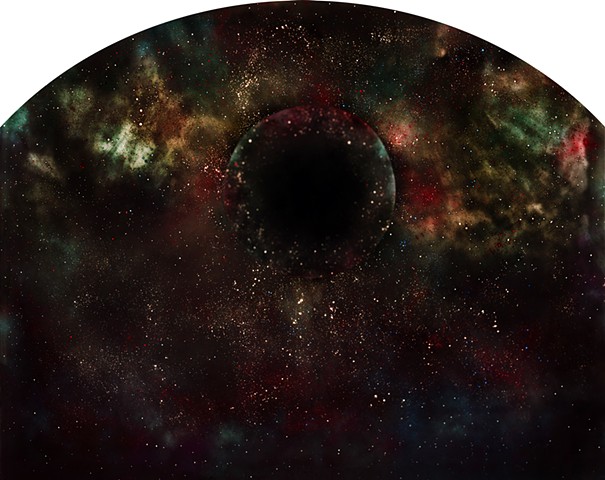

I have thought about this phenomenon in terms of the astrophysical theories regarding wormholes, or the Einstein-Rosen Bridge, which could theoretically bridge two points in space and time that are vast distances away from each other. In Iraq, ISIS has resuscitated Mesopotamian theology by means of destruction. In Tunis, a splinter cell of ISIS carried out an attack against the Bardo National Museum, where a mosaic of Virgil penning the Aeneid suddenly spills into the vast, bloody framework of ISIS’s reworking of the modern Middle East. These brutal tactics allow for figures of antiquity to take on new relevance as they move through a wormhole opened by the contempt they inspire in the Salafist vision of a new Middle East. This investigation into cosmological phenomena will bend into formal visual subject matter in the photographs. I am particularly moved by the bridging of sculpted images from antiquity and the unimaginable scope offered by the photographs taken by telescopes currently hurdling through outer space. The chronological, technical and conceptual distance between these methods of image-making offers a startling contrast of divine images.