We Who Believe in the Unseen

In Qur’anic scripture, the phrase, "al-Ghae’eb," or "the Unseen," constitutes a reality that defines the visible world as nothing more than a veil. This material manifest is woven together into a delicate and wondrous mesh understood by Muslims as the signs of God, or "ayah." This fabrication is the secret code woven into nature which makes up the seen and unseen. Such scripture is the foundation from which stem my questions regarding the phenomenological properties of photography and how it formally and conceptually interacts with Al-Ghae’eb. The arms of this work grow from the core belief that the world is made up of layers both seen and unseen.

Photographs inherently mediate between these two layers by providing the viewer with the mark of a moment that is forever lost and unknowable. In using the camera to record images, we are left with only the sign of a person, place or experience and never the thing itself. A photograph is but the trace of something which no longer exists in its original form; a veil between visage and time. Roland Barthes explores how the photograph operates as the material between these worlds in his 1980 book, Camera Lucida. He describes looking at a photograph of Napoleon's brother, Jerome, taken in 1852: “I am looking at eyes that looked at the Emperor.” My intention with this work is to describe, in photographs, the thin ground separating visible and invisible, spirit, flesh and the curtains in between.

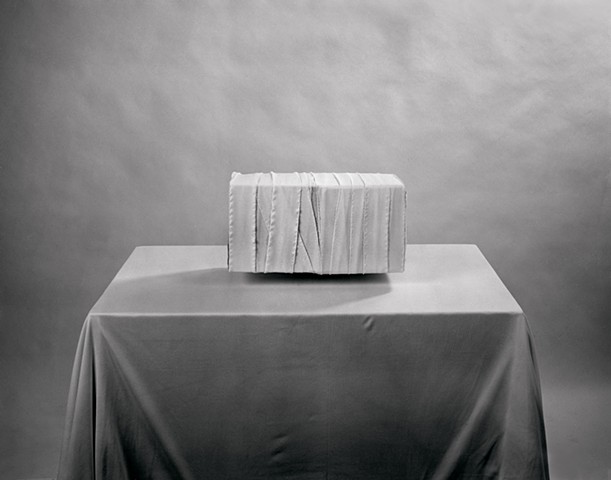

So far, I have attempted to describe this thinness between clarity and concealment using various materials, light, and spacial relationships between the sparse elements that compose each image. Each photograph is a close meditation on delicate tonal shifts and an object’s relationship to presence and absence in tandem with its surroundings. In this regard, every image depicts a different kind of disappearing act.

The photos are also informed by the tension between the very concrete nature of photography and traditional Islamic art’s prohibition of representational imagery. I was concerned with how to reconcile a traditionally non representational, non-figurative form of art with a medium whose very existence is defined by mechanical representation. I began structuring the photographs with allusions to early Sunni architecture and Shi’a illuminations. It is through this language of visual restraint and reverence that I attempted to make images that were as much about ceremony as they were uncertainty.

This work has been shot entirely on an 8x10 view camera. The use of the 8x10 camera signals an era when Western society held the photograph as an empirical form of evidence; something which could finally prove the past as a reality. A subtext hidden within the early promise of photography was another very antiquated promise: that of alchemy. I would like to pick up this thread of transmutation and frame the work inside a tradition that defines photography as an instrument capable of magic. These images are mere representatives of a transformational quality found, at least in earthly materials, within photography alone. And though my chosen materials reflect a disappearing era, the ongoing technological shifts in photography’s materials have yet to abandon these founding characteristics. The photograph still functions as the translator and deceiver of time, flesh, and air. The questions I am asking in regards to these images are but a wish to find even a humble reconciliation between two languages of human experience; the material and the divine. They are images that balance between photography’s history as the evidential eye and Islam’s portrayal of the world as a veil.